By Chisomo Magelegele and Dorothy Bandawe, WASH Project Officers, Water For People Malawi

This blog was a finalist in our first Water For People blog competition among all of our colleagues around the globe. Congratulations Chisomo and Dorothy!

Versión en espanol aquí.

In Malawi, 69% of the population has access to at least basic drinking water sources, and four million people continue to lack access to safe drinking water. Access to improved water in rural communities has predominantly been provided through boreholes fitted with handpumps which have evolved over time. The Afridev handpump has been the most used type of pump for rural water supply due to its low operating and maintenance costs and availability of spare parts in communities.

The main challenge with handpumps has been their inability to reach people who live in upper lands where drilling rigs cannot access. In some areas, saline conditions cause poor water quality, and, in others, geophysical conditions make accessing underground water difficult. These challenges have necessitated a shift in thinking among water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector actors away from water point sources with handpumps toward piped distribution networks. In rural areas of Malawi, Water For People is promoting the adoption of solar reticulated water pumping technology.

Solar powered water pumping has recently garnered significant attention as an alternative technology in rural water supply as they are operationally, financially, and environmentally sustainable. Other technologies traditionally rely on fuel, and electric pumps are costly, difficult to maintain, and environmentally unsustainable. Solar water pumping is a viable way to expand water access across low- and middle-income countries and communities while helping mitigate the effects of shifts in rainfall caused by climate change.

A typical solar powered water system consists of solar panels that absorb solar energy from the sun and convert it into electrical energy through photovoltaic effect. The electrical energy pumps water into a reservoir tank that is raised high above the ground. Gravity pressures water from the tank to various connections at households and institutions.

In the past, operation, and maintenance (O&M) of water supply systems has been sidelined at both institution and community levels, resulting in poor functionality rates. This is mostly due to limited knowledge, skills, and financial resources to manage the system and vandalism. Poor system functionality not only interrupts access to safe water, but it is also associated with increased health risks, lower worker retention at institutional levels (such as health facilities), and decreased education standards due to absenteeism.

In 2019, UNICEF provided solar reticulated water supply schemes in six health facilities and seven primary schools in Chikwawa and Nsanje Districts in response to the water stress these institutions were facing. While promising, provision of the state-of-the-art solar powered water supply infrastructure created challenges related to lack of knowledge, skills, finances, and management arrangements in the institutions to operate and maintain the schemes.

To address these challenges and enhance sustainability, UNICEF partnered with Water For People in Malawi since we work in close collaboration with District Councils to support sustainable management models. The project targeted 13 institutions – seven primary schools, four health centers, and two hospitals – reaching over 4,800 learners and 13,000 community members with safe water. These institutions were selected based on lack of management arrangements for tariff setting and compliance, as well as limited technical knowledge to maintain the solar reticulated systems. Additionally, vandalism and theft of system components such as pumps, panels, and cables were prevalent in these institutions.

Depending on the spatial distribution, design capacity, number of collection points, and existence of Water Users Associations (WUAs), three management models were developed with clear involvement of the private sector, users, and local leadership to ensure sustainability:

- Delegated management model: An existing functional WUA with experience managing energy propelled systems is delegated with management of selective schemes within its catchment area. The District Water Development Officer (DWDO) automatically becomes a member of the Board, and the District Education Manager (DEM) and District Health Officer (DHO) become ex-officio members if scheme hub is in public institutions.

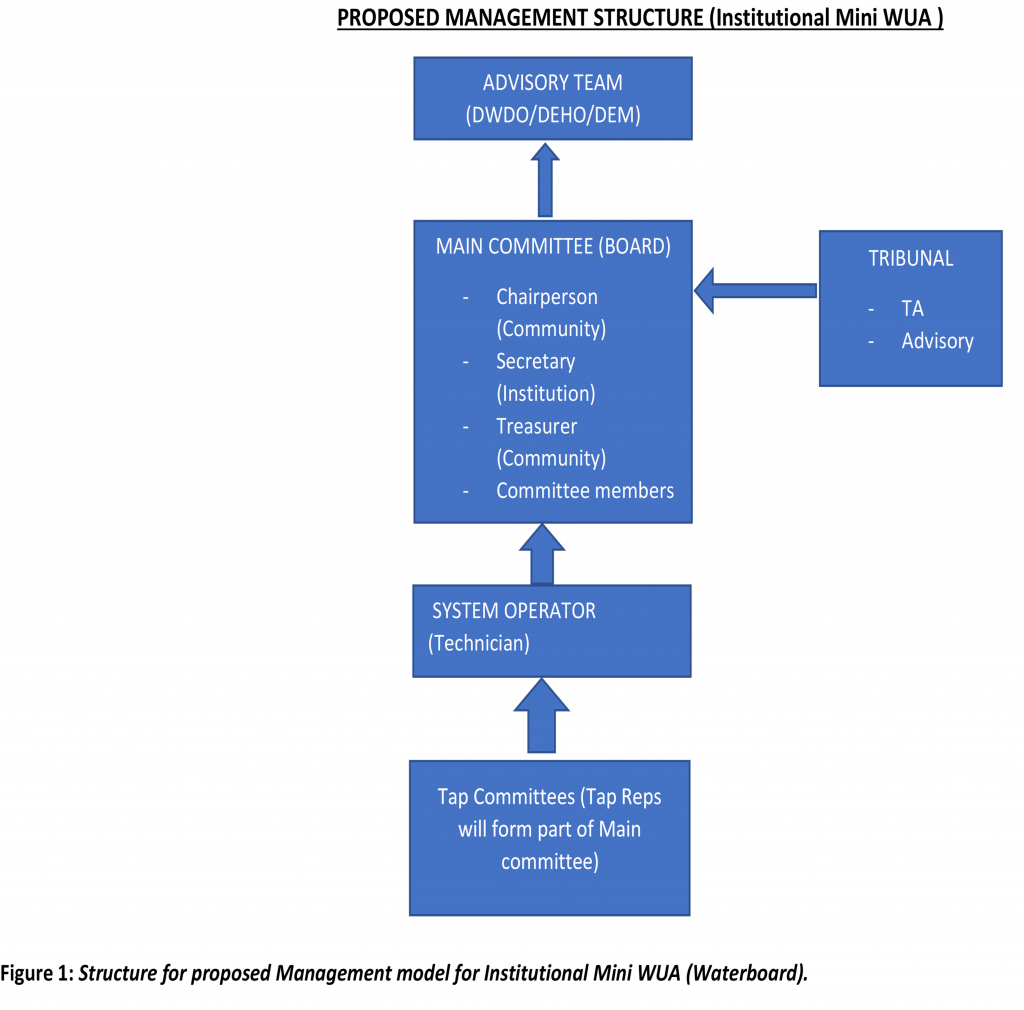

- Institutional water system model: A Board comprised of institution representatives and community members manage the scheme. The DWDO, DHO, and DEM are incorporated as ex-officio members. To minimize operational costs, the Board hires a system operator who is trained on O&M, professional management, tariffing, and financial management.

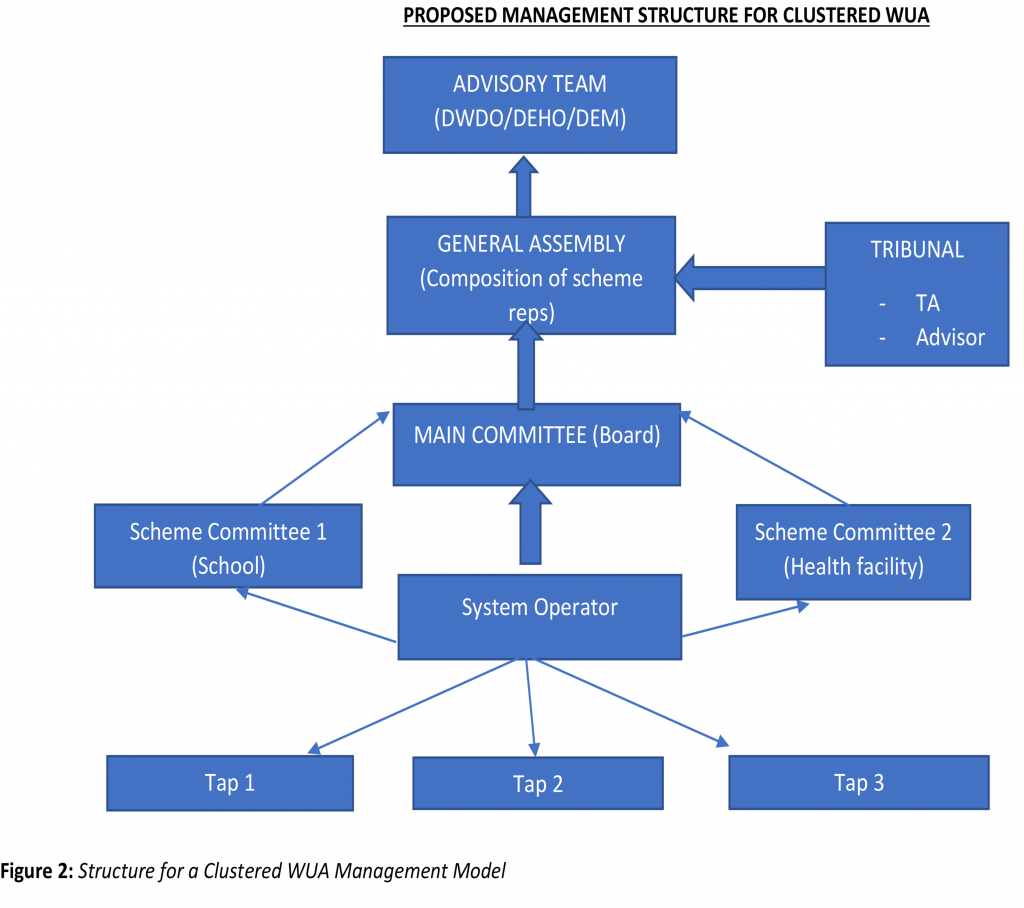

- Clustered mini-WUA model: Several schemes are merged and managed by one utility operator on a performance-based contract. The WUA has an independent Board comprised of community representatives from the beneficiary schemes. The DWDO, DHO, and DEM provide an oversight role as ex-officio members.

Water For People employed different strategies to ensure sustainable management of the solar powered schemes and increased level of service. We conducted a detailed assessment of previous management approaches to adapt the new models. We focused on stakeholder engagement at both district and community levels prior to implementation and development of key performance indicators to track the progress and effectiveness of the management models. Through various engagement meetings with key stakeholders (namely, the District Executive Committee, District Coordination Team, Area Development Committee, and local leaders), management models were adopted by scheme committees to sustainably manage the solar reticulated schemes.

To ensure continued O&M and promote sustainability, the committees have been trained on solar reticulated scheme management. Water For People is linking the schemes to suppliers and private utility operators with expertise in solar powered systems to provide maintenance service for extensive repairs. Prior to the forthcoming mentorship and business plan development sessions, management committees and local leadership are sensitizing communities to encourage payment of user fees and curb vandalism.

Through this development and adoption of management models, capacity building on scheme management, professionalization through private sector involvement, and continuous government and community stakeholder engagement, communities are now contributing tariffs for cost recovery, adhering to a constitution, and have a sense of ownership of the schemes. These strategies are expected to increase water point functionality rates and access in these rural areas.

Leveraging these lessons from the UNICEF project, Water For People has since constructed a new solar powered reticulated system in Traditional Authority Katunga of Chikwawa District, serving over 2,500 people of Ntondeza and Kapasule Villages with safe water.

Previous attempts to drill a borehole in the saline area of Ntondeza have proven futile. As such, Water For People drilled a high yielding well in the neighboring village of Kapasule to supply water to Ntondeza and surrounding communities via distribution lines using a solar powered water system. A WUA has been established for the system, and members were trained on sustainable management of the scheme.

Instituting an effective management system, capacity building on O&M and financial management, and involvement of various stakeholders such as district council officials, local leaders, politicians, and the private sector is vital to ensure the solar powered water systems are sustained. This gives us a better chance of attaining Sustainable Development Goal 6, through increased service levels and sustainability of water services in rural areas of Malawi.

Participants listening to the proceedings during management model engagement meetings (L) and a typical solar powered scheme (R) An illustration of an institutional water system committee (L) and a clustered mini WUA (R).